1 Existing concepts and mechanisms for provenance¶

Processing data with LSST middleware involves executing a directed acyclic graph (DAG) called a QuantumGraph, where each node is either a Quantum, a single execution of a single PipelineTask, or a dataset managed by the Butler.

The datasets produced by executing a QuantumGraph are written to a single RUN collection in the data repository.

The collections that hold input datasets are associated with that RUN collection by defining a new CHAINED collection that includes both inputs and outputs.

A RUN collection is constrained to have at most one dataset of a particular dataset type and data ID; the latter may be empty, implying only one dataset of a particular dataset type per RUN.

This system already provides support for limited provenance recording:

- Dataset types with empty data IDs can be used to store arbitrary information describing a

RUN, as long as it is acceptable to obtain that information viaButler.get(i.e. the information does not need to be used as a constraint on futureRegistrydatabase queries). This is already used to record the configuration of allPipelineTasksbeing executed and list of software names and versions, and a hook allows concretePipelineTasksto store and retrieve their ownRUN-level content, such as the schemas of any catalogs they produce or consume, prior to execution. Any kind of execution harness (including but not limited to BPS implementations) can also store their own per-RUNinformation by defining their own dataset types, without any need to modify lower-level middleware software. - Dataset types with data IDs that match those of a particular

PipelineTask'squanta can be used to store arbitrary information describing a quantum. This is already used to storeTaskmetadata and (in at least some configurations) logs. - The

CHAINEDcollection provides a record of the input collections that were used. - The

QuantumGraphitself is a complete description of the processing that can be used to reproduce aRUNexactly (aside from transient hardware/environment problems, of course), on any system with access to the same datasets and sufficiently similar hardware and software (with the latter verifiable via the per-RUNsoftware versions dataset).

The primary limitation in the current system is that the QuantumGraph is at most saved to a file outside the data repository (at the user’s discretion), and hence much of the provenance we produce is often discarded.

It also only captures predicted inputs and outputs, which are in general a superset of the actual inputs consumed and outputs produced by quanta; this is sufficient for reproduction when starting everything from scratch, but harder to make use of when reproducing subsets or starting from a partial run.

Saving a more complete, as-executed QuantumGraph in the data repository has always been part of the high-level middleware design, and a more detailed design is the subject of the next section.

Before moving on, it is worth pointing out a few issues with the provenance that we do record:

- The software versions we record may not extend far enough into OS- or container-level software to guarantee reproducibility (but by using

condaeven for compilers, the dependence of our code’s behavior on OS- and container-level software should be minimized). - Because we do not assume that the complete set of relevant software packages can be enumerated, and instead rely (at least partially) on what Python packages are imported, running additional processing that brings in new imports against an existing output

RUNcollection requires us to update the versions dataset in place - an operation we otherwise prohibit inButler(datasets are considered atomic and immutable, at least for writes) and simulate by deleting the old one and writing a new one. This is both fragile and incompatible with our plans to distribute Data Release processing across multiple Data Facilities, unless we just prohibit that kind ofRUNcollection extension or do enumerate all relevant software somehow up front. - The approach of using datasets to record arbitrary provenance for higher-level tooling is currently extensible only to the extent that those datasets can use existing storage classes.

New storage classes must currently be registered by editing configuration in the data repository, in

daf_butleritself, or in a location given by an environment variable; while the latter may provide a way to handle user-defined storage classes gracefully, we have not yet identified environment-management practices for this, and at present it is expected that developers modify the default configuration indaf_butler. This is a problem for much more than just provenance, however (it also limits pipeline extensibility), and is something we hope to resolve. - Using

CHAINEDcollections to link input collections to output collections is often assumed to relate input and output datasets that share the same data ID (or have related data IDs). This usually works, at least as far as relating predicted input to predicted output datasets, but only because ourQuantumGraphgeneration algorithm is based on data ID commonality; some otherQuantumGraphgeneration algorithm that is equally valid for execution may not have this property, or may make important exceptions. It also fails when aCHAINEDcollection includes a “merge” of two outputRUNcollections that have conflicting datasets (i.e. they have same dataset type and data ID); dataset lookup then uses the order in which thoseRUNcollections appear in theCHAINEDcollection to resolve the conflict, but this may not correspond to what was actually used as an input, and in fact more than one of the conflictig datasets may have been used as inputs (to different quanta). - Batch execution with BPS may “cluster” multiple quanta into a single “job” to e.g. avoid overheads in acquiring compute nodes or allow local scratch space to be used for some intermediate datasets.

We currently have no way to store job-level provenance in a data repository, except by denormalizing it into per-quantum datasets or merging it externally into per-

RUNdatasets.

2 Saving complete quantum provenance¶

2.1 Representing executed quanta in Registry¶

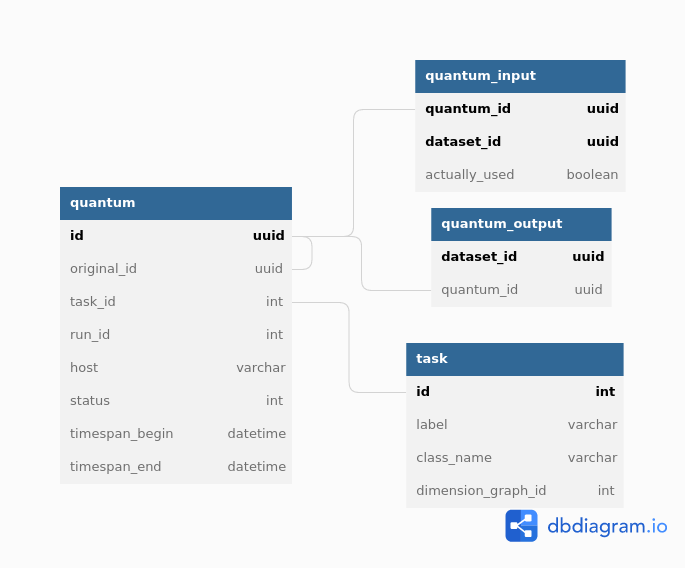

Proposed tables for storing quantum-based provenance in the registry database are shown in the diagram below [source]:

The main new tables for provenance are:

task: each row represents a labeledPipelineTaskconfiguration in aPipeline;quantum: each row represents a single attempt to execute a task.

Like datasets, quanta may be associated with collections, are “owned” by exactly one RUN collection, and there may be only one quantum with a particular data ID and task in each collection.

Instead of storing these relationships in new tables, however, we associate each quantum with a special ${TASK}_quantum dataset (with the same UUID) that contains the full original quantum - at least everything needed to reconstruct what is in the registry tables, as well as additional information that isn’t needed for most provenance queries.

We use this dataset’s collections and data IDs as those of the quantum itself.

This dataset does not need to include all provenance information related to the quantum; the execution system can chose to write arbitrary additional information (e.g. logs) to different dataset types that are related to the quantum in the same way as its regular output datasets (these are still identifiable as special via their dataset types).

The ${TASK}_quantum dataset should not appear as a regular output of the quantum, and it should not be used as an input by any downstream task.

The host, status, and timespan_* columns of the quantum table provide basic metadata about the execution that we consider likely to be search criteria in provenance queries.

The original_id column provides the original UUID for quanta whose executions failed, as described below in 2.3 Failures and retries.

Tasks are not associated with a particular collection, and are uniquely identified by their label (just like dataset types); this means they represent a particular set of task configurations in pipelines that share this label, and have a many-to-one relationship with actual Python PipelineTask types.

Note

It may make more sense to make task labels non-unique, except within a particular collection, in order to allow the label to have different meanings in different pipelines or change its definition more easily over time.

This would be analogous to the RFC-804 proposal for dataset type non-uniqueness, however, and as long as dataset type names are globally unique, and task labels are used to produce dataset type names (e.g. <label>_metadata or <label>_config), there’s relatively little to be gained from making label uniqueness apply only within a collection.

The definition of those dataset types (which must be globally unique) would still effectively force global label uniqueness.

The quantum_output table associates each dataset with the quantum that produced it.

Because a dataset can be produced by at most one quantum, we could put this table’s columns directly into the dataset table itself, but we expect keeping it separate to both improve separation-of-concerns in the Python codebase and make schema migrations easier.

This also permits datasets not associated with quanta (i.e. those ingested from external files, or produced before the provenance system is implemented) to have no rows in this table, instead of adding NULL values to the dataset table.

The Registry database’s quantum_output table includes only output datasets that were actually produced, which is in general a subset of those predicted to be produced by the original QuantumGraph.

Those predicted-only output datasets will be listed in the quantum’s special dataset and can hence still be retrieved, but we do not consider it worthwhile to include them in the Registry as well:

- doing so would also require creating rows in the

datasetanddataset_tags_*tables, and then finding ways to make sure they do not pollute or slow down queries for regular datasets that do exist (or at least once existed); - trimming these datasets from a

QuantumGraphdoes not affect the datasets it will actually produce (and, in fact, it may give us an opportunity to identify and prune out quanta that will do nothing earlier).

Links between quanta and their input datasets are similarly stored in the quantum_inputs table.

This is a standard many-to-many join table with one extension: the actually_used flag.

This may be set to false by PipelineTask implementations (via a new hook in the ButlerQuantumContext class, probably) to indicate that the input dataset was not used at all, i.e. running the quantum without the dataset would have no effect on the results.

Note that this definition considers a dataset to be “used” even if it was used only to determine which other datasets to use more fully, e.g. in some kind of outlier-rejection scheme.

Tasks that do not opt-in to this fine-grained reporting will be assumed to use all inputs given to them.

Note that there are actually three possible states for a quantum input dataset relationship, when the “actually produced” state for outputs is considered as well:

- a dataset is an “actual” input if

quantum_input.actually_usedistrue; - a dataset is merely an “available” input if it is present in the

Registrydatabase (and hence a preexisting dataset or one “actually produced” by an upstream quantum in the same graph), butquantum_input.actually_usedisfalse; - a dataset is a “predicted-only” input if it appears only in the original

QuantumGraphand the${TASK}_quantumdatasets.

This schema does not provide a dedicated solution for associating tasks with the InitInput and InitOutput datasets they may consume and produce during construction.

Our preferred solution is to introduce a special “init” quantum for each task.

This quantum’s inputs would be the InitInputs for the task, and its outputs would be the InitOutputs for the task as well as provenance datasets (configuration, software versions) written by the execution system itself.

It would have an empty data ID instead of the usual dimensions for the task, and be distinguishable from other quanta by having a different dataset type for its special quantum dataset (e.g. ${TASK}_init vs ${TASK}_quantum).

This approach will need to be reflected in the in-memory QuantumGraph data structure and the execution model; these special init quanta would be executed prior to the execution of any of their task’s usual quanta, which would be handled naturally by considering at least one task InitOutput (the config dataset is a logical choice) to be a regular input of the task’s regular quanta.

This is actually more consistent with how BPS already treats the init job as just another node in its derived graphs, but with one init node per task, rather than one init node for the whole submission.

Having one init quantum per task provides a solution to current problem we raised earlier: if we write a different software version dataset for each (per-task) init quantum, instead of one for the entire RUN, each can be handled as a regular, write-once dataset, instead of needing to simulate update-in-place behavior.

2.2 Recording provenance during execution¶

Avoiding per-dataset or per-quantum communication with a central SQL database is absolutely critical for at-scale execution with our middleware, so the provenance described above will need to be saved to files at first and loaded into the database later.

Most of the information we need to save is already included in the QuantumGraph produced prior to execution, especially if we include UUIDs for its predicted intermediate and output in the graph at construction.

We are already planning to do this for other reasons, as described in the “Quantum-backed butler” proposal in [3].

Always saving the graph to a managed location during any kind of execution (not just BPS) is thus a key piece of being able to load provenance into the database later.

The remaining information that is only available during/after execution of a quantum is

- timing, status, and host fields for the

quantumtable; - a record of which predicted outputs were

actually_produced; - a record of which predicted inputs were

actually_used.

These can easily be saved to a file (e.g. JSON) written by the quantum-execution harness, and here the design ties again into the quantum-backed butler concept, which also needs to write per-quantum files in order to save datastore record data.

In order to allow these files to serve as the long-term ${TASK}_quantum datasets, we would also need to duplicate the data ID and collection information from the original QuantumGraph within them.

Just like the provenance we wish to save here, the eventual home of those datastore records is the shared Registry database, so it is extremely natural to save them both to the same files, and upload provenance when the datasets themselves are ingested in bulk after execution completes.

In fact, these per-quantum files may also help solve yet another problem; as described in DMTN-213, our approach to multi-site processing and synchronization will probably involve metadata files that are transferred along with dataset files by Rucio, in order to ensure enough information for butler ingest is available from files alone. These provenance files could easily play that role as well.

Our proposal is to only load provenance into the Registry database if the execution system has at least attempted to run them.

Quanta whose executions were blocked by failures in upstream quanta would not be included, even if present in the original QuantumGraph.

This leaves room for them to be added by later submissions of the same graph (or subsets thereof) without any UUID conflicts.

The quantum-backed butler design is a solution to a problem unique to at-scale batch processing, so writing the QuantumGraph and datastore-records files to BPS-managed locations (such as its “submit” directory) there is completely fine.

That’s not true for provenance, which we want to work regardless of how execution is performed.

This is related to the long-running middleware goal of better integrating pipetask and BPS.

It will probably also involve carving out a third aspect of butler (a new sibling to Registry and Datastore) for QuantumGraph and provenance files, because

- like

Datastore, this aspect would be backed by files in a shared filesystem or object store (but not necessarily the same filesystem or bucket as an associatedDatastore); - like

Registry, the new aspect would provide descriptive and organizational metadata for datasets, rather than hold datasets themselves, and after execution its content would be completely loaded into theRegistry.

The full high-level design will be the subject of a future technote, but an early sketch can be found in Confluence. A key point is that ultimately we want inserting datasets back into a permanent registry to be a deferred, final step in all modes of execution, not just BPS, allowing that step to transform file-based data in various ways before it is loaded into a database.

Recording provenance only when using BPS (and relying on it to manage the QuantumGraph and provenance files) in the interim seems like a good first step.

Extending the design to include non-BPS processing may take time, but we do not anticipate it changing what happens at a low level, or the appearance of persisted provenance information.

2.3 Failures and retries¶

When a quantum fails during execution, we will often want to try running it again.

This may happen immediately via workflow system functionality or manually via a resubmission.

The outputs of any such failure are considered unreliable, and we don’t want to proceed with downstream processing even if some outputs were written before the failure (not producing all - or even any - outputs is not necessarily considered a failure).

We want actual failures to be included in provenance, and their datasets included in the main data repository, until/unless they are explicitly deleted after any analysis of the failure is complete.

This leads to a conflict: running a failed quantum again would lead to two quantum rows with the same UUID, data ID, and RUN, and analoguous conflicts for any output datasets that were written before the failure occurred or in spite of it (e.g. logs written by the execution system after it catches an exception).

The possibility of immediate retries performed by the workflow system means we cannot assign the retry quantum and datasets new UUIDs, because this would prevent downstream quanta from being able to find their inputs.

Instead, we have to assign new UUIDs (and a new RUN collection) to the failures, and move all datasets that were already written to permanent storage out of the way.

This could be done immediately after the failure occurs if we have a process able to do the work (i.e. the worker process fails gracefully, or some control process is able to take action), or it could be done only just before actually attempting a retry.

When automatic retries still do not succeed, or are not even attempted, it probably makes sense for the BPS transfer job (or a similar operation in other execution contexts) to do this itself, ensuring that the original QuantumGraph can also be used for manual retries without requiring anything to be modified in the permanent data repository.

In all of these cases, the failed quantum and its output datasets (predicated and actual) should ultimately be ingested into the registry database with their new UUIDs and RUN collections, with the quantum.original_id column holding the original UUID of the quantum.

This may or may not reference another row in the quantum table, depending on whether the quantum eventually succeeded.

We can also choose to simply drop failed quanta and their output datasets, especially if they have a straightforward and uninteresting failure model. This could be done by the “transfer” job when these cases can be detected automatically, or even when a retry is first attempted. As a default, however, we feel it is safer to gather failure provenance and artifacts whenever possible up front, and leave whether to retain them permanently up to human operators.

2.4 Interfaces for querying quantum provenance¶

Given the similarity between quanta and datasets in terms of table structure, a Registry.queryQuanta method analogous to queryDatasets provides a good starting point for provenance searches:

def queryQuanta(

self,

label: Any,

*,

collections: Any = None,

dimensions: Iterable[Dimension | str] | None = None,

dataId: DataId | None = None,

where: str | None = None,

findFirst: bool = False,

bind: Mapping[str, Any] | None = None,

check: bool = True,

with_inputs: Iterable[DatasetRef] | None = None,

with_outputs: Iterable[DatasetRef] | None = None,

**kwargs: Any,

) -> QuantumQueryResults:

...

Most arguments here are exactly the same as those to queryDatasets,

with the dataset type argument replaced by a label expression identify the tasks, and two new arguments to constrain the query on particular input or output datasets.

Like queryDatasets, the return type would be a lazy-evaluation iterable, with convenience methods for conversion to QuantumGraph instance; this type could also be returned by a new DataCoordinateQueryResults.findQuanta method to more directly find quanta from a data ID query (as the findDatasets does for datasets).

Note

This signature should be interpreted as an example of a possible queryQuanta method’s capabilities, not a detailed interface specification.

The existing Registry methods are likely to see substantial changes in the direction of fewer keyword arguments and more method-chaining and expression parsing before the provenance query system is implemented, and we expect its design to follow suite.

This interface does not provide enough functionality for most provenance queries, however - it just finds all quanta matching certain criteria, regardless of their relationships - so it is best considered way to obtain a starting point. For those, we envision an operation that starts with a set of quanta and traverses the graph according to certain criteria, querying the database as necessary (perhaps once per task or dataset type) and returning matching quanta as it goes:

def traverseQuanta(

self,

initial: Iterable[Quantum],

forward_while: Optional[str | TraversalPredicate] = None,

forward_until: Optional[str | TraversalPredicate] = None,

backward_while: Optional[str | TraversalPredicate] = None,

backward_until: Optional[str | TraversalPredicate] = None,

) -> Iterable[Quantum]:

...

Traversal could proceed forward (in the same direction as execution) or backward (from outputs back to inputs) or both. The criteria for which quanta to traverse and return are encoded in the four predicate arguments, which are conceptually just boolean functions on a quantum:

class TraversalPredicate(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def __call__(self, quantum: Quantum) -> bool:

...

Traversal would be terminated in a direction whenever a while predicate evaluates to False (without returning that quantum) or whenever the corresponding until predicate evaluates to True (which does return that quantum).

This simple conceptual definition of the predicate may not be possible in practice for performance reasons; traversal actually involves database queries, and while we can perform some post-query filtering in Python, we want most of the filtering to happen in the database.

In practice, then, we may need to define an enumerated library of TraversalPredicates, and perhaps define logical operations to combine them, restricted to what we can translate to SQL queries.

Most common provenance queries could be satisfied by the following predicates and their negations (even if they cannot be combined):

- whether the quantum’s task label is in a given set;

- whether any input or output dataset type is in given set;

- whether any input or output dataset UUID is in a given set.

- whether the quantum or any input dataset is part of a particular RUN collection.

It’s also worth considering variants of this interface that are given a single callback object with multiple methods, with ways for that object to control not just whether to proceed forward or backward but which dataset connections to follow in detail.

It is worth noting here that the Quantum and QuantumGraph objects returned here are not necessarily the same types as those used prior to execution; execution adds more information that we want the provenance system to be able to return.

Whether to actually use different types involves a lot of classic software design tradeoffs involving inheritance and container classes, and resolving it is beyond the scope of this document.

If we do use different types, one of the most important operations on the “executed” forms will of course be transformation to a “predicted” form for reproduction.

2.5 Intentionally inexact reproduction¶

Quantum-based provenance excels at exact reproduction of previous processing runs, but it can also be used - with some limitations - to re-run processing with intentional changes.

The most straightforward way to reprocess with changes is to create a completely new QuantumGraph.

The software versions and task configuration stored in per-RUN datasets can be combined with the special “init” quanta for each task to reconstruct the pipelines used in a RUN exactly, and of course other versions or configurations may be used instead as desired.

The input collections and data ID expression also typically provided as input to the QuantumGraph generation algorithm are not directly saved in our provenance schema, however, because after execution we intentionally do not draw any distinctions between quanta that may have originated in different graphs as long as their outputs land in the same RUN (and hence have the same software versions and configuration).

Higher level tools such as BPS or a campaign managements system may nevertheless save this information in their own datasets, along with any other graph-building or per-submission information relevant for those tools.

Changing software versions and configuration while keeping the input datasets and data IDs the same can be more directly accomplished using quantum-based provenance.

The former is what happens naturally when a different version of the codebase is used to fetch and run a stored QuantumGraph, while the latter can easily be expressed as mutator methods on the QuantumGraph object (or perhaps arguments to the code that transforms an already-executed provenance graph into a ready-to-run predicted graph).

There is one large caveat: different versions and configuration can lead to different predictions for inputs and outputs for a quantum, and when applied to a full graph, this can result in some quanta being pruned either because they are no longer needed to produce desired target datasets or because it can be known in advance that they will have no work to do.

In some cases, it should logically expand the graph instead - but if we are starting from provenance quanta and are not re-running the QuantumGraph generation algorithm in full, we cannot in general add fundamentally new quanta, though we may be able to identify ways to do so for specific use cases in the future.

This depends on how our algorithm for QuantumGraph generation evolves; our current algorithm has essentially no way to incorporate existing quanta, but a long-planned (but long-delayed) new algorithm should be much more flexible in this regard.

Changing the input collections before re-executing a QuantumGraph obtained from provenance would work in much the same way, and would have very similar limitations in the sense that pruning the graph is straightforward but expanding it is not.

Unlike version and configuration changes, updating the graph to reflect new input collections involves querying the Registry, and doing this efficiently (in particular, avoiding per-quantum queries) will make this more difficult to implement.

Changing the input data ID expression while starting from quantum provenance does not make sense in the same way; the right way to think of this is that the data ID expression is instead used in performing the provenance query to fetch those quanta.

It is worth noting that these queries are not affected by the original boundaries of the QuantumGraph objects used for production - a QuantumGraph obtained from provenance can include quanta from multiple RUN collections as well as multiple QuantumGraph-generation submissions within a single RUN collection.

Note

These multi-RUN provenance QuantumGraphs cannot be translated one-to-one into runnable predicted QuantumGraphs, as long as our execution model expects all writes to go into a single output RUN collection with consistent configuration and versions for all quanta within it.

The most straightforward way to address this would be to make the process that translates provenance graphs into predicted graphs a fundamentally one-to-many operation, requiring users to run each per-RUN predicted graph on its own.

Another approach would be to allow a single QuantumGraph to span multiple RUN collections.

Finally, for unrelated reasons (e.g. RSP service outputs, user-defined processing, unusual processing for commissioning), we are considering expanding the data ID / dimensions system to allow custom data ID keys or relax the dataset type + data ID unique constraints, which would also open up new ways of saving configuration (e.g. multiple init quanta per RUN, each with its own config datasets), and that may in enable execution of QuantumGraph objects with heterogeneous configuration.

2.6 Mapping to the IVOA provenance model¶

Our quantum-dataset provenance model has a straightforward mapping to the IVOA provenance model [5], which is also based on directed acyclic graph concepts.

Our “dataset” corresponds to IVOA’s “Entity”, and our “quantum” corresponds to IVOA’s “Activity”.

The fields of these concepts in the IVOA have fairly obvious mappings to the fields of our schema (unique IDs, names of dataset types and tasks, execution timespans).

One important field that may be slightly problematic is the Entity’s “location” field, which might usually map to a Datastore URI, but cannot in general, because our datasets may not have a URI, or may have more than one.

The IVOA terms are more general, and we may want to map other concepts to them as well (e.g. a BPS job may be considered another kind of Activity, and a RUN collection could be another kind of Entity). But none of the other potential mappings are as clear-cut or as useful as quantum-Activity and dataset-Entity.

There are two natural relationships defined by IVOA between an Activity and an Entity, which map directly to the kinds of edges in our QuantumGraph:

- an Activity “Used” an Entity: a quantum has an “input” dataset;

- an Entity “WasGeneratedBy” an Activity: a dataset is an “output” of a quantum.

These relationships have a “role” field that is probably best populated with the string name used by a PipelineTask to refer to the Connection.

Because this role will be the same for all relationships between a particular dataset type and task, it also makes sense to use IVOA’s “UsedDescription” and “GeneratedDescription” classes to define these roles in a more formal, reusable way.

IVOA recommends certain predefined values be used for those descriptions when they apply (e.g. “Calibration” as a “UsedDescription”), which could be identified by configuration that depends on the pipeline definition.

IVOA also defines a “WasInformedBy” relationship between two Activities and a “WasDerivedFrom” relationship between two Entities.

These may be useful in collapsed views of the QuantumGraph in which datasets or quanta are elided, but in our case they can always be computed from the Activity-Entity/quantum-dataset relationships, rather than being graphs we would store directly.

IVOA has no direct counterpart to our “predicted” vs. “available” vs “actual” categorization of quantum-dataset relationships. Because a relationship can have at most one associated “GeneratedDescription” or “UsedDescription”, we cannot use one set of description types for the role-like information and another for this categorization. It seems best to simply leave this out of the IVOA view of our provenance, and possibly limit the IVOA view to “actual” relationships, since it is not expected to play a role in actually reproducing our processing.

We currently have no concept that maps to IVOA’s “Agent” or any of its relationships.

3 Addressing provenance working group recommendations¶

Italicized bullets in this section are specific recommendations quoted from [1]. Middleware responses are in regular text below.

3.1 Recommendations relevant to quantum provenance¶

- [REC-SW-3] Software provenance support should include mechanisms for capturing the versions of underlying non-Rubin software, including the operating system, standard libraries, and other tools which are needed “below” the Rubin software configuration management system. The use of community-standard mechanisms for this is strongly encouraged.

- [REQ-WFL-005] Both the OS and the OS version must be recorded. This requirement may be met within the pipeline task provenance, but it is an upscope since currently, only the OS type is recorded.

The existing software-version recording logic used in PipelineTask execution (implemented in lsst.utils.packages) does extend to non-Rubin software, and it does use community-standard mechanisms when possible.

But it also relies heavily on bespoke methods for obtaining versions for certain packages, and it is unclear to what extent this is historical (i.e. predating our use of conda for the vast majority of our third-party dependencies), as well as for deciding when to use various different community-standard mechanisms.

The code should at least be carefully reviewed for possible simplification and generalization.

- [REQ-PTK-001] As planned, complete the recording of as-executed configuration for provenance.

This is already implemented.

- [REQ-PTK-002] As planned, complete the storage of the quantum graph for each executed Pipeline in the Butler repository.

This will be satisfied by implementing the design described in [2.1 Representing executed quanta in Registry] and [2.2 Recording provenance during execution].

- [REQ-PTK-003] Code and command-line support for recomputing a specified previous data product based on stored provenance information should be provided.

This will be satisfied by implementing the design described in [2.4 Interfaces for querying quantum provenance].

- [REQ-PTK-004] A study should be made on whether W3/VO provenance ontologies are a suitable data model either for persistence or service of provenance to users.

This is discussed extensively in [2.6 Mapping to the IVOA provenance model]. To answer the question posed here directly, mapping to the IVOA data model is entirely suitable as one way to serve provenance to users, but it is slightly lossy and should neither be our way of storing quantum provenance internally nor the only way we serve this provenance to users.

- [REQ-PTK-005] URIs (as well as DataIDs) should be recorded in Butler data collections.

This recommendation requires clarification before we can comment on its implementation in middleware.

The butler Registry associates each dataset with a data ID and at least one collection, but collections do not store data IDs directly.

The butler’s Datastore component may associate a dataset with one or more URIs, but this is not guaranteed in general, and even when present these URIs are not always sufficient information to be able to reconstruct an in-memory dataset.

These URIs may also use an internal form that is not usable by science users.

So, while there may well be (and will generally be) URIs involved in dataset storage within butler data repositories, they do not play an important role in provenance, and while some interpretations of this recommendation are trivially satisfied by the current middleware design, these interpretations are not consistent with a recommendation relevant to provenance, and it seems more likely that the intent was both more related to provenance and is probably not satisfiable by the middleware.

- [REQ-WFL-001] Logs from running each quantum must be captured and made available from systems outside the batch processing system.

- [REQ-WFL-002] Any workflow level configuration and logs must be persisted and made available from systems outside the batch processing system. This information should be associatable with specific processing runs.

The PipelineTask execution system already includes support for saving logs to butler datasets.

That satisfies these requirements in a minimal sense, but we expect higher-level workflow tools to do a better job of saving logs (in addition or instead) using third-party tools better suited for log analysis.

This is already the case at the IDF.

- [REQ-WFL-003] Failed quanta must be reported including where in the batch processing system the quantum was running at the time of failure.

This will be satisfied by implementing the design described in [2.1 Representing executed quanta in Registry] and [2.2 Recording provenance during execution], provided the host field in the quantum table is consistent with the “where” question here.

- [REQ-WFL-004] Though no requirement exists, it should be possible to inspect, post-facto, the resource usage (CPU, memory, I/O etc.) for individual workers.

This is already implemented for provenance queries that start with the data ID of the quantum to be inspected, because these values are stored in the task metadata dataset (at a coarse level by the execution system, and optionally with more fine-grained information by the task itself). The rest of the design described in this document should allow this information to be connected with worker nodes.

3.2 Observatory-Butler linkage¶

Possibly relevant recommendations:

- [REC-EXP-1] As planned, program details known to the scheduler (such as science programme and campaign name) should be captured by the Butler.

As long as these details are included in the FITS headers of the raw files, they can be configured to be capture by the butler and stored in the exposure dimension table.

This is already the case for the fields used as examples in this recommendation.

- [REC-EXP-2] As planned, OCS queue submissions that result in meaningfully grouped observations should be identified as such in the Butler.

3.3 Metrics linkage¶

- [REC-MET-001] For metrics that can be associated with a Butler dataId, the metrics should be persisted using the Data Butler as the source of truth. The dataId associated with the metric should use the full granularity.

- [REC-MET-002] Any system that uses Butler data to derive metrics should persist them in the Butler provided that the metrics are associable with a Data ID.

This is already implemented and in regular use in the faro and analysis_tools packages, and is currently the only way that metrics derived from butler data are initially stored.

It is arguable whether the butler datasets are considered the source of truth after upload to SQuaSH ([2]).

[4] will explore these details more fully.

- [REC-MET-003] When lsst.verify.Job objects are exported, the exported object should include the needed information (run collection and dataId) to associate with the source of truth metric persisted with the Data Butler.

At present it is unusual for butler datasets to store their own data ID and especially their own RUN collection internally, but this is something we expect to do more often in the future (see discussion on REC-FIL-1 below).

It might make more sense for metric values persisted to butler data repositories to be saved as a dataset that does not have this state, and for the system that exports it to SQuaSH to combine the dataset content with the data ID and RUN collection from the Registry.

- [REC-MET-005] Even if effort for implementation is not available in construction, we should develop a conceptual design for structured, semantically rich storage of metrics in the Butler.

We currently save metric measurements as individual YAML files, which is convenient for upload to SQuaSH but inconvenient for querying metric values via the butler.

We are in the midst of a transition to a format that stores multiple metric measurements in a single JSON dataset, which is much more efficient but no better for queries.

It also precludes using thresholds on metric values at criteria in QuantumGraph generation.

A custom Datastore backed by by either the Registry “opaque table” system or SQuaSH itself (along with Registry query system extensions) would make butler queries against metrics much more convenient and efficient.

[4] will again provide more detail on this subject.

This will be easier if we can normalize the content in metric datasets with what is in the Registry and generally make them smaller and more consistent, in essence unifying the lsst.verify data model with the butler one:

- Each

lsst.verify.Metriccan be mapped directly to a butler dataset type, so there should be no need for a metric measurement to store itsMetricinternally. - The opaque blobs associated with an

lsst.verify.Measurementshould probably be factored out into separate butler datasets with different dataset types when measurements are stored in the butler. - An

lsst.verify.Jobis a container for a group of measurements, and is probably best not mapped directly to anything stored by the butler, but a higher-level factory forJobinstances that uses the butler to query for and fetch measurements and blob data may be useful, especially as a way to upload to SQuaSH.

(Note that these Job types have no relation to the BPS job concept.)

This mapping is very much preliminary, and is based on a fairly superficial understanding of the lsst.verify data model.

A more detailed design should be included in [4].

3.4 Saving provenance in dataset files¶

- [REC-FIL-1] Serialised exported data products (FITS files in the requirements) should include file metadata (e.g. FITS header) that allows someone in possession of the file to come to our services and query for additional provenance information for that artifact (e.g. pipeline-task level provenance).

Low-level I/O for files written by the butler goes through the lsst.daf.butler.Formatter interface, which could be easily extended to include external dict-like metadata that should be recorded in the file.

That metadata should be passed through a new optional keyword argument to Butler.put, and can be prepared by the execution system to include provenance information.

As implied by the recommendation text, this could only be implemented in formatters that use data formats that can store flexible metadata, but this should be true in practice for any data format used for public data products (including FITS, Parquet, and JSON, provided this external metadata can be cleanly separated from the file content itself).

To satisfy [REC-FIL-1], all we need to store is the dataset’s UUID, which (after implementing the design described in [2.2 Recording provenance during execution]) will be available to the execution system for insertion into the provenance metadata when the dataset is first saved to disk, and quite easy to pass into the code that actually writes the files. It might be useful to also save the UUID of the producing quantum, and it may be worth also recording the UUIDs of all datasets input to the quantum (grouped by dataset type) as well, to possibly avoid the need for full provenance queries in the simplest cases. This may be less useful than it seems or perhaps even slightly confusing in some cases, however, because:

- as of the time a dataset is written, we can only reliably know the “available” inputs to the quantum; the task may later declare that only some of these inputs were actually used;

- in a few cases (large gather-scatter sequence points in the graph), the number of inputs to the quantum may be large (in the case of FGCM, a full-survey sequence point, it will be enormous);

- there is no guarantee that the datasets directly input (as opposed to transitively used as inputs via some predecessor quantum’s outputs) to a quantum constitute scientifically interesting provenance.

At this time, it seems prudent to save only the dataset and quantum UUIDs, absent a clear use case for saving more.

- [REC-FIL-2] A study should be made of the possibility of embedding a DataLink or other service pointer in the FITS header in lieu of representing the provenance graph in the file.

The formatter hook described in the previous subsection would clearly be capable of embedding such a link in the file when it is first written, but doing so effectively declares that the service pointer can

- be calculated from some combination of information (dataset UUID, data ID, dataset type,

RUNcollection, URI(s)) known to the execution system or formatter; - be assumed to remain static over the lifetime of the file.

These seem like dangerous assumptions, in that satisfying them probably either creates unwanted dependencies between software components (the execution system has to be configured to know about RSP service endpoints) or puts undesirable constraints on others.

Injecting this metadata into files when they are retrieved seems much cleaner conceptually, but it may rule out simple and/or efficient approaches to data access that would otherwise be on the table. We would not consider this kind of implementation of this recommendation to be a middleware responsibility.

3.5 Provenance recommendations not directly relevant to middleware¶

To the extent that these recommendations describe best practices or conventions, we believe middleware provenance systems will be consistent with them, but they do not directly map to any current or planned functionality.

- [REC-EXP-3] Any system (eg. LOVE, OLE/OWL) allowing the entering or modification of exposure-level ancillary data should collect provenance information on that data (who, what, why).

- [REQ-TEL-001] Investigate ways to expose all information in the Camera Control System Database to the EFD.

- [REQ-TEL-002] The MMSs should ideally have an API and at the very least a machine-readable export of data that would allow its data to be retrieved by other systems.

- [REQ-TEL-003] Any new CSCs (and wherever possible any current CSCs that lack them) should have requirements on what provenance information they should make available to SAL so it can be associated with their telemetry.

- [REC-SW-1] There are a number of extant versioning mechanisms in DM and T&S software environments. Care should be to not proliferate those unreasonably but to share software versioning and packaging infrastructure where possible. As these systems are hard to get right, the more teams use them, the more robust they tend to be.

- [REC-SW-2] All systems should have individual explicit requirements addressing what, if any, demands there are to be able to recover a prior system state. When such requirements are needed, the systems should have to capture and publish in a machine-readable form, version information that is necessary to fulfil those requirements. Such requirements should cover the need for data model provenance, eg. whether it is necessary to know when a particular schema was applied to a running system.

- [REC-SW-4] Containerization offers significant and tangible advantages in software reproducibility for a modest investment in build/deploy infrastructure; it should be preferred wherever possible for new systems, and systems that predate the move to containerization should be audited to examine whether there is a reasonable path to integrate them to current deployment practices.

- [REC-FIL-3] Irrespective of ongoing design discussions, every attempt should be made to capture information that could later be used to populate a provenance service.

- [REC-SRC-001] Perform a census of produced and planned flags to ensure that 64 bits for sources and 128 bits for objects are sufficient within a generous margin of error. This activity should also be carried out for DIASources and DIAObjects source IDs.

- [REC-SRC-002] We are concerned that merely encoding a 4-bit data release provenance in a source does not scale to commissioning needs and the project should decide whether it is acceptable for additional information beyond the source ID to be required to fully associate a source with a specific image.

- [REC-SRC-003] More generally, a study should be conducted on whether 64 bit source IDs are sufficient.

- [REC-SRC-004] Although not provenance-related, we recommend that the DPDD be updated to clearly state whether footprints and heavy footprints are to be provided.

- [REC-MET-004] A plan should be developed for persisting metrics that are not directly associated with Butler-persisted data.

- [REC-LOG-1] Since time is the primary provenance element for a log entry, systems are to produce (or make searchable) in UTC.

- [REC-LOG-2] Each site (summit, IDF, USDF, UKDF, FRDF) should provide a log management solution or dispatch to another site’s log management service to aid log discoverability.

- [REC-LOG-3] Individual systems should make clear log retention requirements.

4 Implementation notes¶

This technote should be mined for Jira epics and stories after it has been reviewed by stakeholders, but we can comment now on how to sequence the implementation of the quantum-level provenance that is its primary focus:

- implementing the quantum-backed butler design from [3] (see tickets attached to DM-32072). This will set up up the overall data flow needed for provenance recording, at least when BPS is used.

- Design Python classes for representing “already executed”

QuantumandQuantumGraphobjects (which will entail changes to the existing “predicted” variants of these, including the introduction of “init” quanta), and start writing these when quantum-backed butler is used in execution (i.e. when BPS is used). This should include serialization compatible with writing executed quanta to the per-quantum files written by the quantum-backed butler (probably via Pydantic/JSON). - Add

Registrysupport for storing quantum-level provenance, using the schema proposed here, possibly with modifications identified in the previous step (which is why that step is worth doing first). This probably needs to include simple quantum query support for testing purposes, but it shouldn’t need to include the more complicated graph traversal system. Perform schema migrations in major repositories. - Update the BPS “transfer” job to ingest provenance from quantum-backed butler’s per-quantum files into the registry.

- Add full

Registrysupport for querying provenance, including graph traversal. - Extend

pipetask(or replacement tools) to write provenance to the registry when running outside of BPS as well, and include predictedQuantumGraphobjects and quantum-backed butler output files in a new third butler component. This needs a much more complete design that is beyond of this technote.

The sequencing becomes less clear for later steps, but generally this allows us to start writing provenance as early as possible in the most important context (BPS execution).

References

| [1] | [DMTN-185]. Frossie Economou, Gregory Dubois-Felsmann, Keith Bechtol, Robert Gruendl, Simon Krughoff, Brian Stalder, and Amanda Bauer. A Survey of Provenance. 2021. Vera C. Rubin Observatory Data Management Technical Note. URL: https://dmtn-185.lsst.io/ |

| [2] | [SQR-008]. Angelo Fausti. SQUASH QA database. 2016. Vera C. Rubin Observatory SQuaRE Technical Note. URL: https://sqr-008.lsst.io/ |

| [3] | (1, 2) [DMTN-177]. Tim Jenness. Limiting Registry Access During Workflow Execution. 2021. Vera C. Rubin Observatory Data Management Technical Note. URL: https://dmtn-177.lsst.io/ |

| [4] | (1, 2, 3) [DMTN-203]. Tim Jenness. Tracking Metrics in Butler. 2021. Vera C. Rubin Observatory Data Management Technical Note. URL: https://dmtn-203.lsst.io/ |

| [5] | Mathieu Servillat, Kristin Riebe, Catherine Boisson, François Bonnarel, Anastasia Galkin, Mireille Louys, Markus Nullmeier, Nicolas Renault-Tinacci, Michèle Sanguillon, and Ole Streicher. IVOA Provenance Data Model Version 1.0. IVOA Recommendation 11 April 2020, April 2020. |